Hawzah News Agency – When Venerable Sanathavihari was ordained as a Buddhist monk eight years ago, it was a lonely experience. As a young Mexican American who grew up Catholic in Los Angeles’ Koreatown, he didn’t know many other monks he could relate to.

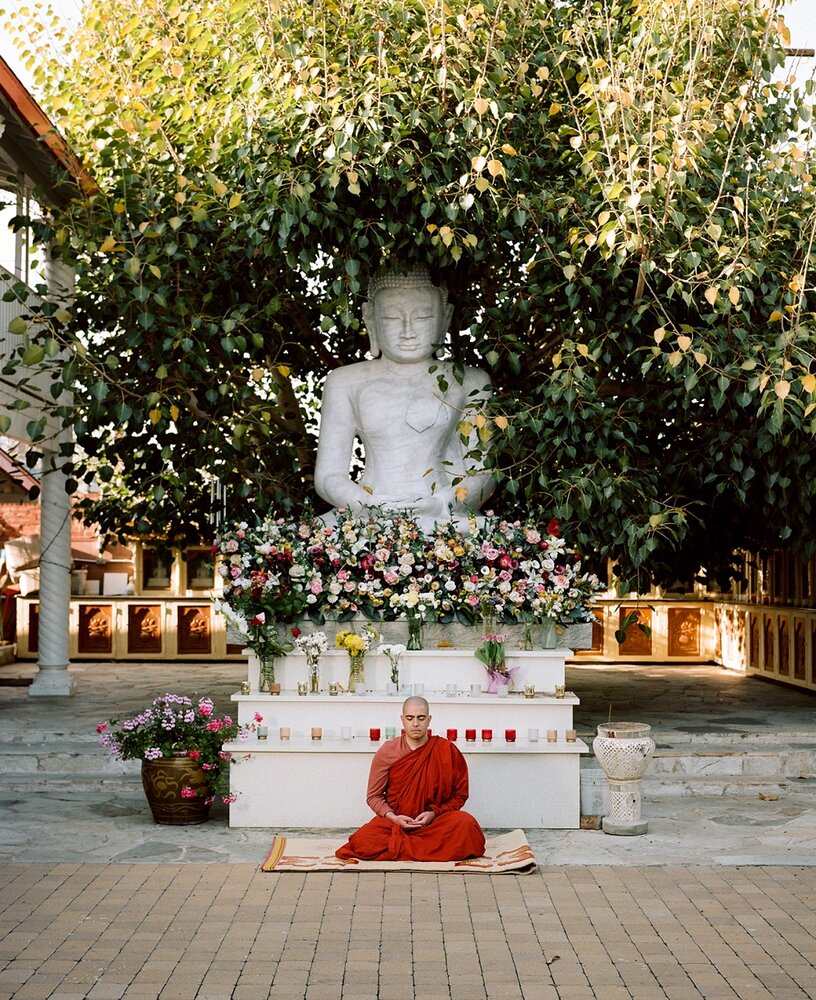

But since then, he’s helped build a flourishing Latino Buddhist community at Sarathchandra Buddhist Center in North Hollywood, a temple founded by Sri Lankan Americans. The temple now has two Latino monks and another in training – thought to be the most at any temple in LA – as well as a growing number of Latino laypeople who help sustain temple life.

Sanathavihari said these shifts could represent a real turning point for a community that often faces language and cultural barriers when trying to learn about this ancient religion.

“That potential and openness for Buddhism to be fully integrated into the Latino culture of southern California is starting to happen,” Sanathavihari, 37, said, “so it doesn’t become something foreign, or other, or fetishized – it’s just like, ‘Oh yeah, this is just something that Latinos do, they can be Christian, Catholic, Buddhist or whatever.’”

Sanathavihari, who spent nine years in the air force before being ordained at 29 in the Theravada tradition – one of the major branches of Buddhism typically practiced in Sri Lanka and south-east Asia – said he aspired to make the religion more accessible. Before the pandemic moved everything online, he established Casa de Bhavana, a global virtual community of Latino Buddhists with resources – including meditation videos, translations and explanations of Buddhist practices and teachings – in Spanish. He’s even hosted several retreats in Mexico and recently helped open a Buddhist center in the Canary Islands in Spain.

Offline at the temple, he said, he speaks to practitioners in Spanish and counsels Latinos who may relate to him more than the Sri Lankan monks. He also tries to spark curiosity by walking around the neighborhood and riding the bus and train in his robes. Newcomers to the temple usually find it through word of mouth.

“I don’t preach. I don’t try to convert people,” he said. “But I want to increase visibility to let people know that we’re here, that Buddhism in Spanish is here.”

It’s unclear how many Latino Buddhists there are in the US. Pew Research Center estimated that in 2014, 12% of Buddhists in the US were Latino, based on a survey of just 262 people. Even less clear is whether – or to what extent – the number of Latino Buddhists has grown in recent years. But anecdotal evidence suggests a tide of new interest.

Sanathavihari said most of the temple’s new members were young Latinos, and that they were engaging more in communal and ritual aspects of temple life. “Before, when Latinos would come, they’d stay to learn meditation and that’s it,” he said. “But now they want to be part of it and contribute to it and take on the roles of traditional Asian Buddhists in the community.”

Diana Herrera, 31, said she had become interested in Buddhism years ago but avoided temples because she felt out of place and couldn’t communicate with the other monks. She hadn’t experienced this at Sarathchandra, however, and started going regularly about three years ago. She now attends weekly meditation and study sessions, had recently organized a mindfulness hike and assists the monks by bringing them any items they need and cleaning the temple.

“I like helping the monks because it helps others also,” she said.

This year, Michael McPherson, 67, started his novice monk training at the temple, a three-month period before ordination that includes meditation, chanting, studying the Buddha’s teachings, ritual prayers and blessings for the community and temple chores.

McPherson, a former investment banker and father of two adult sons, said becoming a monk would let him eliminate life’s distractions so that he could focus on his studies and service. “It’s amazing how we overwhelm ourselves with responsibility – and for what?” he said. “All of that is cut off, is let go of when a person goes into monastic life. Just that internal feeling of happiness, of calmness, of serenity – it’s amazing.”

Sanathavihari said several factors contributed to Latinos’ growing interest in Buddhism, including the country’s continuing shift away from Christianity, and the way the pandemic and Black Lives Matter protests have led people to re-evaluate their lives and open themselves up to new spiritual practices and ways of thinking.

At Sarathchandra, representation has also been key. “When they see another Latino there, it’s like, ‘OK, this can be for me. I can step outside of my culture and embrace another culture without feeling like I’m betraying my culture.”

Venerable Dhammasudassi, 44, another Mexican American monk at the temple, agreed.

“As human beings, if we see somebody who is from our culture or who looks like us, and they are following this teaching, or they’re doing this kind of practice, we automatically have more interest in it,” the LA native said. “And as monks we feel like we can relate to the experiences of other people in the community because we come from that community.”

Sarathchandra isn’t the only Buddhist temple with a growing number of Latino practitioners. Sanathavihari said that when he visited other temples across the city, he often met fellow Latino Buddhists. And outside temples, many others are turning to Buddhist practices such as mindfulness and meditation in a more secular context.

Rosamaría Segura first learned about meditation when she was working at an LA non-profit serving Central American refugees. Many of them had post-traumatic stress disorder, and to help them cope she started translating guided meditation tapes into Spanish.

“At some point I realized, wow, this is so beneficial, I wonder why nobody’s teaching it in Spanish,” said Segura, now a teacher in the meditation community InsightLA.

She made it her mission to bring mindfulness – which she called a “tool for self-care and understanding” – to underserved Spanish-speaking communities that typically aren’t exposed to it. Before the pandemic, she said, she taught a meditation class at a flower shop in a busy marketplace in East LA. While not a traditional meditation space, it met the people where they were.

“We just sat there in the middle where you could hear all the restaurant workers doing the pots, they were listening to the soccer games, and people would still come and sit and practice,” she said. More recent in-person meditation sessions have been held at a salsa dance hall, alongside a food distribution program in South Central LA, and at a school where the students’ mothers can join.

Sanathavihari, who is also pursuing a master’s in bilingual counseling, said finally having fellow Mexican American monks and a thriving lay community was a “relief”, since it alleviated his workload of pastoral care for the Latino community and gave him a new sense of companionship. He credited the work done by Sri Lankan monks at Sarathchandra, who had been reaching out to Latinos in the neighborhood decades before he arrived, he said. “I’m just helping those flowers bloom.”

He hopes his presence will inspire young Latinos to think outside perceived cultural norms and expectations – and not just to become Buddhist.

“They might see me and not want to become a monk, but it might open their mind to, like, ‘Wait a minute, if this guy can do this, maybe this other dream I have, I can do that, too.’”

Your Comment