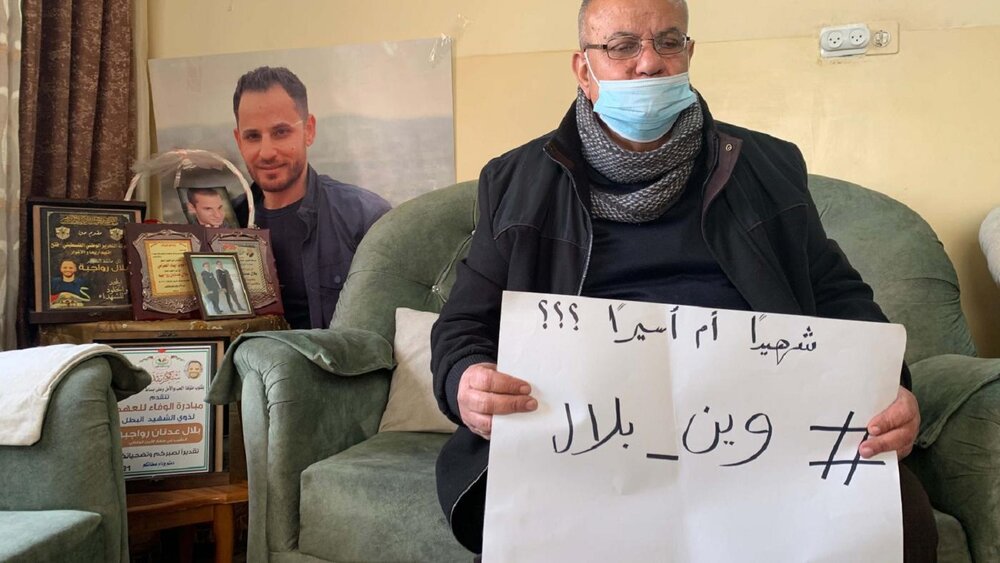

Hawzah News Agency –At every protest they attend, in every social media post, in all of their correspondence with NGOs and official bodies, the Rawajba family from Nablus in the Israeli-occupied West Bank have one burning question.

Where is Bilal?

For 14 months, the family has sought the answer everywhere they turned but to no avail. All they hope to find out is whether he’s dead or alive.

On 4 October 2020, the Israeli intelligence called the Rawajba family, who live in the village of Iraq al-Tayah near Nablus, informing them that the Israeli army shot their 30-year-old son while he drove by the Huwara military checkpoint outside Nablus.

The first call from the Shin Bet, Israel’s internal security agency, confirmed that Bilal was wounded, an account confirmed by eyewitnesses who informed the family that a helicopter had arrived at the site and taken Bilal away.

Only half an hour later, the Shin Bet summoned Bilal’s father, Adnan Rawajba, to Huwara, where he was subjected to a field interrogation that focused on Bilal’s social life.

After repeated questions from Adnan about his son’s whereabouts, the interrogators eventually told him that Bilal was taken to an Israeli hospital.

“They told me that Bilal is injured, and that he was taken to Tel Aviv to receive treatment at the hospital, and they refused to tell me the name of the hospital or to update me on his health status,” Adnan told MEE.

Shortly after he was released by the army, Adnan received another call telling him that his son had died. When he reached his home, his daughter told him that they received another call saying that the news about Bilal’s death was incorrect, and that he was still receiving treatment.

The lack of clarity in the army’s answers has left the family worried and confused for more than a year. Now, they are speaking out about his disappearance, hoping to put pressure on Israel to reveal Bilal’s fate.

No one to turn to

The Rawajba family have not left a stone unturned in their search for their son.

Bilal, a father to one daughter, is a graduate of police science from Mubarak Military Academy in Egypt, and has worked as a legal advisor to the Palestinian Preventive Security Forces (PSF) in Tubas at the rank of a captain.

Maha Rawajba, Bilal’s sister, says the family has knocked on many PA doors, including the PSF, pressuring them to use the PA’s coordination with Israel to find some answers.

The family is demanding that Israel hand over Bilal’s body if he is dead, so that they may bury him. If he is alive, they want to visit him and check up on his health.

“We were a normal, stable family,” Adnan told MEE.

“But now our lives have completely changed; we are living out our worst days because of all the uncertainty and pain. The fact that we don’t have an answer to Bilal’s fate is a kind of collective punishment to us as a family.”

The family has been in contact with local and international human rights organisations over Bilal’s case, Maha told MEE, and now they want to take it to international courts.

Maha has also launched an online awareness campaign under the hashtag ‘Where Is Bilal?’ (وين_بلال#), saying “indifference of official institutions” left them no other option.

The Israeli army told MEE they are checking details of Bilal’s case when approached for comment. No further details were provided at the time of publication.

‘Collective punishment’

Similar agony of not knowing the fate of loved ones shot by the Israeli army is shared by many families in the West Bank.

Suheir Barghouthi believes her son was killed by the Israeli army in 2018 near Ramallah. But the 62-year-old has yet to see his body and no death certificate has been issued for him, an open wound that continues to haunt her three years later.

“As a mother, I’m living this pain every day, because I want to know what happened to my son,” Barghouthi told MEE.

“I’m prepared to accept that he is dead, but I need to be sure of it by seeing his body, and to allow me to bury him, or at least to know where he’s buried.”

Saleh Barghouthi, 29, who worked as a taxi driver, was shot by a special forces unit of the Israeli army in the village of Surda, north of Ramallah on 12 December 2018.

Saleh was suspected of carrying out an attack near the Ofra settlement three days earlier which left two Israeli soldiers dead and injured others.

Eyewitnesses confirmed to Suheir Barghouthi that Saleh was wounded during the arrest and was walking on his feet when transported away from the location.

An investigation by leading Israeli rights group B’Tselem concluded that Saleh was shot point-blank in an “apparent extrajudicial killing”.

“We have not seen Saleh, either martyred, injured, or imprisoned. This created a mystery surrounding his fate,” Suheir told MEE. “It has put us in a state of constant pain.”

Without an official death certificate for Saleh, his family’s life has been disrupted. As a result, his eight-year-old son Qays cannot obtain many official papers, including registration in school.

Saleh’s widow remarried and had a daughter, but she couldn’t issue her a birth certificate without Saleh's death certificate.

Israel’s ambiguity about the fate of Palestinians like Saleh is a deliberate form of “collective punishment”, Suheir says.

“It would seem that Israel revels in witnessing the suffering of entire families that cry out demanding to know what has become of their sons.”

Withholding bodies

Israel’s policy of withholding bodies of Palestinians or information about them is intended to avoid conducting an autopsy that would involve the PA or the Red Cross, said Asem Aruri, director of the al-Quds Centre, or JLAC, a human rights organisation.

“Detaining bodies and using them as bargaining chips constitutes human trafficking, and is an international crime,” Aruri told MEE.

JLAC, which is working to reclaim the bodies of missing Palestinians, has documented 93 cases, including seven children and three women, where Israel withheld bodies of Palestinians since 2014.

An additional 254 bodies have been withheld in Israel’s "cemeteries of numbers" since 1967, although the Israeli army admits to the existence of 120 of them in numbered graves, Aruri said.

Your Comment